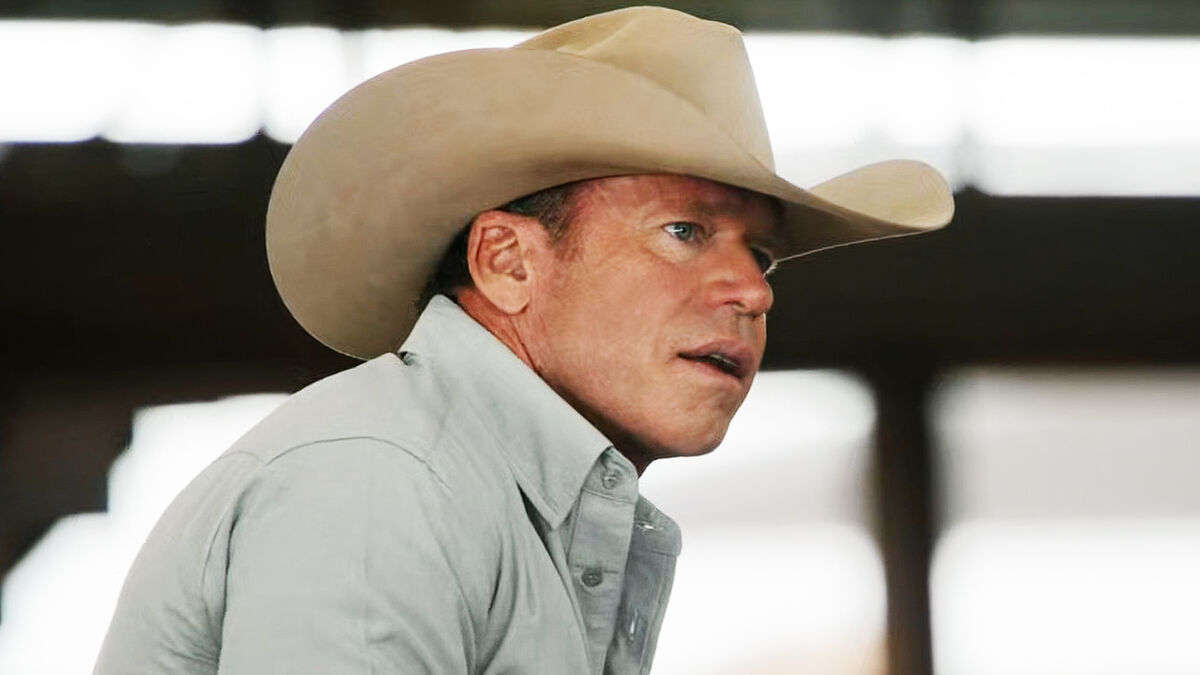

The Cowboy God Who Said No: Taylor Sheridan Dismantles His Own Legend

In a smoky room lit by raw honesty, Taylor Sheridan, the man behind Yellowstone’s violent beauty and billion-dollar legacy, leaned forward and said the unthinkable:

“I’m just not that f***ing special.”

For a generation of fans who built shrines to his name, who saw him not just as a screenwriter but a keeper of American mythology, this wasn’t just humility. It was heresy. But for Sheridan, it was the only truth that mattered.

🪓 From Rejection to Reverence

Few remember that Yellowstone was initially rejected by HBO—labeled too harsh, too old-fashioned, too anti-establishment. Sheridan, a former actor turned screenwriter, had already made waves with Hell or High Water and Sicario. But Yellowstone was personal. A Western without sentiment. A family drama without redemption. He bet everything, wrote it his way, and walked when studios asked him to compromise.

The result? A modern TV empire.

1883, 1923, Tulsa King, and the upcoming Y: Marshals all grew from that soil. And yet, Sheridan sees no genius in it. He calls Yellowstone a “horse opera that makes no sense.” In his words:

“It’s not trying to [make sense]. It’s a window into a world… I subtracted from that in 1883 and tried to make it look slightly more foreign.”

He credits instinct over brilliance. Curiosity over cleverness. For Sheridan, the success wasn’t planned. It was survival.

🔥 The Storyteller Who Refuses the Throne

Sheridan’s fans see him as a mythmaker—the last great cowboy riding through a scripted landscape of recycled plots and safe endings. But when asked about the cult-like devotion he inspires, his answer is razor-sharp:

“If something’s interesting to me, it’s probably going to be interesting to a lot of other people… I just don’t think I’m that unique.”

He speaks with the detachment of a rancher counting cattle—not followers. He rejects celebrity, rejects credit, and rejects control. For him, storytelling is still manual labor. And Yellowstone isn’t legacy—it’s work well done under pressure.

But whether he likes it or not, he’s become the outlaw everyone wants to follow.

🌾 The Empire That Grows in Spite of Him

Despite his discomfort with praise, Sheridan’s numbers don’t lie.

-

Yellowstone has pulled in billions in revenue for Paramount.

-

It reshaped the streaming landscape, proving that gritty Western drama could dominate in the age of superheroes and sci-fi.

-

It revived Kevin Costner’s career, gave Kelly Reilly and Cole Hauser cult status, and birthed a cultural universe that rivals Marvel in scope, if not tone.

All this, from a man who shrugs when asked about his influence.

All this, from a writer who insists he’s just chasing what feels real.

Yet he still writes. Still builds. Still expands.

Whether it’s 1923’s bitter colonial dust, or Y: Marshals’ lawless frontier, Sheridan keeps returning to the well he claims isn’t that deep.

Maybe that’s the secret. He digs not for glory—but because he can’t stop carving story from soil.

🦬 Legacy, Refused. Power, Accepted.

Sheridan’s refusal to be idolized doesn’t erase his impact. In fact, it sharpens it. We live in an era where most creators chase virality. Sheridan chases silence, violence, and landscapes that scar the soul.

He speaks like a man who knows too much about control—and wants none of it.

But whether he admits it or not, his characters—John, Beth, Rip, Jamie, Kayce—have become totems of modern identity. Symbols of loyalty, betrayal, and the price of standing still while the world turns modern around you.

He may not want the throne. But he built the damn castle.

❖ Final Ride: The Prophet Who Walks Away

In rejecting worship, Taylor Sheridan doesn’t shrink. He solidifies. There’s something uniquely American about a man who creates a kingdom, opens its gates to millions, then walks back to his horse and says, “Don’t thank me.”

And maybe that’s why Yellowstone works. Not because it’s perfect. But because it was built by someone who didn’t care about being perfect. Just honest, ruthless, and unapologetically Western.

He doesn’t want to be called a god.

But hell, he’s written enough of them into existence.